Prefer to listen?

This blog post forms the basis of a podcast on our new coaching model, which you can listen to here.

What is the SCARF model?

In a previous article and podcast we talked about neuroscience and how having an awareness of certain areas of it could be really useful to us as coaches. One model that came about as a result of some neuroscience research is the SCARF model. It’s not specifically neuroscience, but it uses research from neuroscience in a model that is accessible and useful and worth thinking about in the coaching room.

The research (by the likes of Matthew Lieberman and Naomi Eisenberger) that SCARF is based on is in the area of social neuroscience: that’s the exploration of what goes on in our brains and our nervous systems when we’re engaged in social groups and social interactions with others.

The SCARF model itself was developed by David Rock, a leadership consultant and coach when he was doing a doctorate in the neuroscience of leadership. It’s about how we respond to social interactions and what he describes as the organising principle of the brain; Basically, we’re constantly searching out rewards like food, and trying to minimise threats. Whilst we talk about it as neuroscience, there’s actually some evolutionary science in there as well. It’s going back to our animalistic nature and those natural drives we have within.

What would the SCARF model be useful for in the coaching room?

I think probably the most common way that you would use it is if someone’s talking about a threat response; whether they speak directly about one or you recognise that in them. For example, they might start to get agitated when they talk about something, or they’ll talk about a difficult situation and their reaction to it, and perhaps, because you have an awareness of this concept, you realise that are in ‘threat response’ territory. It could be a difficult situation with someone at work, or within any social environment, or that they’re stressed, or maybe angry about something. You might introduce the SCARF model at that point.

What is the SCARF model?

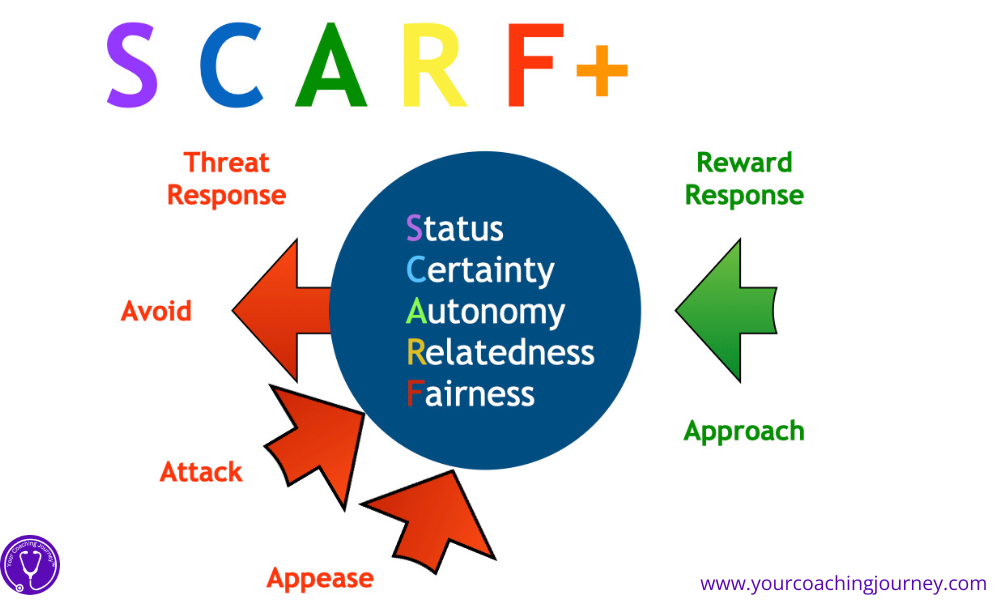

NOTE: We’re going to share both the SCARF model and SCARF+ which is the same, but with some tweaks by Tom – and we’ll explain why he has added them.

SCARF is about five different domains.

- Status

- Certainty

- Autonomy,

- Relatedness and

- Fairness

David Rock’s idea is that these are the five areas of social interaction that are most likely to lead to a threat response and most likely to lead to a reward response.

If we are having a threat response within a social situation, he says that we move away from that social group. There’s an ‘away from’ or avoid response.

And if we are having a reward response, then we will move towards the social group, we become more involved because we’re having those chemical reward responses, so the group is giving us something that we need.

You can see in this adapted model, SCARF+ there are two other threat responses: Attack and Appease which we will explore next.

Why SCARF+?

In our podcast and blog on conflict styles, we spoke about Karen Horney, a German psychotherapist who had ideas about neuroses and defence mechanisms. She had the idea that we have three different defence mechanisms as humans:

- a towards response: appeasing, accommodating, trying to make things right

- an away from response: moving away from the situation, person or group

- an against response: this is where we might want to argue it out and fight against it

So, Tom tweaked the SCARF model to include these, because it just makes sense that these could very well be the reactions of some people. In his original SCARF model, David Rock suggests that a threat response instigates a move away from the group, and that might very well be the case eventually, but in the moment it could well be that you move against the group. Perhaps you stand and argue your case, or you might try the appeasing approach. You might think ‘I really need to belong to this social group, so I’m going to try harder, I’m going to fit in more’.

You can understand the principle that if you get a reward response, you’re going to move towards whatever it is. That’s what we do when we’re searching for a reward. If we were after food, we keep going till we find the food, and we’ll return to where we found the food last time, to see if there’s more. If we’ve got a threat response, then it’s probably going to be unhelpful to us, so we will try to avoid it.

Obviously, as humans, we have that need for connection and to be part of the in-group and to belong, for safety, comfort, support and more. But it doesn’t take an awful lot in any one of these five domains for the equilibrium to be upset and for us to feel like we’re no longer as much a part of the group as we thought we were.

Let’s look at the domains individually:

S is for Status

Status is about where we fit in the hierarchy of a group. It’s not particularly helpful, in modern terms, to talk about hierarchy. People don’t like hierarchy, but hierarchies do exist. They exist within primate groups. And it’s deeply embedded in us that there is a hierarchy. So even in quite a flat structure, there will still be people that have some status and people who are listened to because of that.

If we are being reprimanded in front of other people by the ‘leader’ of the group, a manager, for example, then we will have a threat response and whatever our defence mechanism is, whether it’s against, towards or away from, will kick in.

If we’re receiving feedback, even if it’s constructive feedback, we will quite often have that threat response. It doesn’t take much for that status to be impacted.

On the other hand, if we’re being praised in front of other people or we’re being promoted, then we will have a reward response and we will feel kindly towards the people in that group and we’ll want to belong more and we’ll try harder to belong.

C is for Certainty

There’s a lot of research around change and how people respond to change and that people don’t like change, they don’t like uncertainty or surprises, which I think is true up to a point. But people like the surprises they like.

And people don’t always like absolute certainty because it can become monotonous.

Tony Robbins talks about the six needs that we have as humans. And the first one is certainty, a need for certainty. And the second one is uncertainty, because if we have complete certainty, life just becomes a bit tedious for some people.

Someone who’s low on the conscientiousness scale and high on the openness scale in terms of personality traits will probably want a bit more uncertainty in their life, bit of spontaneity. But it’s one of those domains that if you think about organisational context and social groups, again, people like to know where they are in the social group. So, if there’s a degree of uncertainty going on; a restructure within an organisation, a merger, or potential redundancies it creates uncertainty. People tend not to be told what’s going on. The not knowing, the uncertainty around not knowing can be really problematic for people and will often produce a threat response. Once they know what’s happening, that tends to help ease things, even if they know that they’re going to be leaving the organisation, having the certainty that that’s happening tends to help.

During times of uncertainty it could also be that a team has to work together and therefore may become more you more cohesive. This could lead to a reward response within the group if you’re all in it together, which could be really helpful during a crisis.

Certainty is something that will come up in the coaching room, especially when change is happening. People will be having some reaction to it. They might like it, particularly if they’re going to benefit from the change that’s happening, or they might not.

A is for Autonomy

This is the idea that we like to feel that we have some control over our lives and our daily activities, and we don’t really like to be micro-managed or being told what to do. Within a social group, if this is happening, that is going to produce a threat response for us. In the coaching room if someone has been told they are micro managing their team, or indeed, someone is being micro managed, we can help them to understand what’s going on for them in that situation.

Daniel Pink, who’s a thought leader around motivation recognises that the three main motivators for us as humans are mastery (being good at what you do) autonomy, (being left alone to get on with it) and purpose, (understanding why it’s important that you do what you do and it has some meaning for you). If we feel threatened as far as our autonomy is concerned, and we’ve got someone watching over us, giving us feedback all the time, then that’s not helpful and we will probably have a threat response to that. Whereas if we’re given more autonomy, as long as it’s not, ‘well, you run the whole thing and we’ll leave you alone to do it and it’s ten people’s work’, as long as it’s not that, then we will probably have a reward response to being given some autonomy.

R is for Relatedness

This is how we relate to the other people in the group. And obviously, there may be situations where we get on with most people, but there’s one person we don’t particularly get on with and we probably avoid them a little bit or argue a lot with them. It doesn’t necessarily impact on the rest of the group, but it could easily do so. You could have a disagreement with someone, and they may talk to other people and then it spreads and you become part of the ‘out’ group and there’s an ‘in’ group that doesn’t agree with you.

It doesn’t take much for us to feel like we belong or we don’t belong. Henri Tajfel, a social psychologist, did some work around what is required for us to feel like we belong. And it didn’t take very much. He did a study with students where he split them into two groups and said, okay, you’re in the Kandinsky group and you’re in the Klee group. Just the names of two modern artists and the participants were told they were in those groups. It didn’t mean anything. They didn’t have to do anything. And then they were given this challenge of splitting up some money and they had to apportion money to people in the different groups and they gave more to the people that they were told were in the same group they’d been assigned to. So if they were in the Kandinsky group, they actually gave more money to them, even though they had nothing to do with them. That was all it took, just being told they were in that group.

The point is that we do want to connect, we want to belong, and we will look for those connections in our social group. And if we feel like we’re being isolated or alienated from that group, that will have a threat response for us. And the more connection we can find with people, the more rewarding it is for us.

F is for Fairness

Within organisations this is going to come up time and time again because people will have a perception of what’s fair and it might not be the same as someone else’s perception of what’s fair. In personality work, it’s thought that people with a thinking preference tend to think fairness is treating everyone equally, so treating everyone the same, that’s fair. People that have a feeling preference, it’s thought that they see fairness as treating everyone as individuals, so giving them what they need individually, that that’s fair. There are different nuanced views on fairness and they’re open to interpretation within a social group. But people certainly know when they feel things aren’t fair.

It could be that you see someone else being treated badly and that sense of fairness kicks in for you and you leap to their defence. It’s not necessarily about you being treated unfairly, but people do have a sense of fairness.

Franz Deval, a Dutch/American biologist and primatologist works with primates and he had some monkeys that he was feeding grapes and cucumber to. The one that gets the grapes is very happy and the one that’s fed cucumber is quite happy with cucumber until he realises the other one’s getting grapes and suddenly is very, very upset that he’s getting cucumber. The video is worth a watch:

It seems that it’s deeply wired in us that we want things to be fair and unfairness can trigger a reaction within us.

How Do We Use SCARF+ in the coaching room?

It only takes one domain to be impacted for someone to feel that things aren’t right for them, and that’s probably what’s going to show up in the coaching room.

If we feel an exploration using SCARF+ will be useful, we can simply draw this model out, and explain it, as a little psycho-educative piece within the session: For example, this is a model that comes from social neuroscience and it looks at the domains that might be impacted for anyone when they’re having some reaction in a social group. We can then do a quick review of the 5 domains, and ask them something like ‘which of these do you think is being impacted for you?’ People will have some idea of what’s going on for them and you can then coach around what’s happening, how they see their situation, and perhaps taking a view on how others’ might see it from their own perspective.

We have a great example of using this model to gain perspective on a situation in our podcast on this topic. If you want to jump straight to it, go to 25 minutes and 50 seconds.

SCARF+ helps to develop new understanding. We’re not telling our clients which of their domains are being impacted and which ones of someone else’s being impacted, but asking them to think about it and think in a new way generates some new thinking and perspective about their situation, all of which can be transformative.

SCARF+ is one of many models that we teach and explore on our Doctors’ Transformational Coaching Diploma.

To find out more about our Doctors’ Transformational Coaching Diploma click through here